Imagine you must rewrite the school accountability system and find a new way to judge primary and secondary schools. Do you keep the SATs exams for 11-year-olds? Do you change them to be teacher assessments? What would be your solution?

Before you decide it would probably be a good idea to find out what is happening in the current system. Hence, we polled teachers over the past few weeks about the way SATs run in their schools and their views on effectiveness. Secondary teachers, if you think this doesn’t sound like it matters to you – don’t forget these tests are the baseline for your performance metrics too!

Frankly, we found that a lot of teachers are not happy, there are some pretty massive issues which call into question whether SATs are an effective foundation for judging schools.

SATs Reform: A divide worse than Brexit

If you think that re-imagining SATs exams is easy, think again! Teachers are as split on it as they are on Brexit – just over a third of you would keep formal testing at age 11 (37%), the rest want to dump it.

But, among those of you keen to flee SATs, most would replace them with moderated teacher assessments (also 37%) however the rest would have nothing at all (26%).

This is not helpful! It means that whatever way a politician jumps, the majority will be against them.

Who wants moderated assessment? Primary teachers and secondary English/arts teachers are most keen. However, maths and science teachers are most keen on tests! This is probably not surprising given it’s easier for science and maths to have objective mark schemes.

[But note our questions don’t ask about SATs specifically – more about the idea of SOME tests at age 11].

There are also enormous differences in which primary teachers are keen to switch away from testing at age 11.

Year 6 teachers are keenest to keep official exam-style tests, perhaps recognising how onerous teacher assessment would be! Those who teach the youngest children are less keen on tests – but is this because they find it harder to imagine what it is like for 11-year-olds to sit them?

Are SATs even reliable?

Despite the fact that around a third of teachers want to keep SATs exams… they’re not so convinced the results are reliable! In fact, 72% of secondary teachers do not feel SATs are a reliable measure of pupil attainment.

Senior leaders are more positive about their accuracy, but this is potentially because it is in their interest to feel this way. After all, they have to defend the results.

Why don’t teachers believe SATs results?

The biggest problem for primary teachers is that they feel SATs only measure a very narrow range of academic capabilities (51%), while 43% feel that children are excessively drilled for SATs, and 26% commented on the excessive support for the writing coursework.However, a few mentioned more worrying things – excessive or inappropriate support during the tests themselves.

Secondary teachers are much more negative about the accuracy of SATs. They are less concerned about the narrow testing of academic capabilities and are far more concerned about excessive drilling or excessive support during tests.

Once again, maths and science teachers were most positive about the accuracy of the tests. Note how pretty much all secondary teachers are concerned about excess drilling but that English teachers are particularly concerned about ‘excessive support’ given to achieve standards.

There is a genuine problem for secondary schools if primary pupils are achieving exam results in their SATs which are unsustainable in GCSEs which have more stringent rules around guidance and support.

What about cheating in SATs? (Or ‘maladministration’ as it is technically called)

Under the current arrangements, good SATs results are compulsory but professional integrity is optional.

Solomon Kingsnorth, ‘SATs are not fit for purpose‘

At the end of 2018, a headteacher and two of their staff were forced to leave a London primary school after an internal investigation found that SATs papers had been systematically altered and missing answered added.Of course, it is in everyone’s interest – from the academy chain involved, to the Unions whose members were accused, through to the Department for Education and Standards and Testing Authority – to claim this was a one-off. But was it?

The Department for Education defines maladministration as any act that leads to outcomes that do not reflect pupils’ unaided work or actual abilities. Whilst rumours abound that ‘maladministration’ is common, the number of reported cases each year is tiny but rising.We found that 1-in-5 of our panel who were involved in SATs say they’ve seen something tantamount to maladministration. Of our panel, 13% say they either did, or were asked to, provide a pupil with a reader or scribe under pretence of ‘normal classroom practice’; 10% pointed out an incorrect answer to a child; 6% allowed a class extra time for a test; 5% pronounced spelling in ‘helpful’ ways.

And those who are not on the Senior Leadership Team are more likely to report that this has happened to them.

Secondary teachers regularly hear stories from their students about what went on during SATs. Stories are often just stories, but we were still interested to hear what students were saying. 4-in-10 secondary teachers say they have heard a story from a pupil to suggest that maladministration went on during SATs.

A deep-dive into the readers and scribes issue

Schools are able to give students a reader or a scribe (or both) if they struggle to access the test paper. (NB – they cannot have a reader for the reading comprehension paper.)

The guidelines are clear this must only happen if it is consistent with ‘normal classroom practice’ for this student. However, our data suggests the use of readers or scribes during SATs vastly outstrips the number of teaching assistants in Year 6 classrooms. It seems very unlikely that all these pupils therefore routinely have an adult sitting next to them helping them access school work.

Now, the number of children using readers or scribes is related to school size. The more pupils you have, the more you are likely to use. But we can see that about half of all one-form entry primary schools had at least four students using either a reader or scribe. Just imagine if one-sixth of our primary children really did have this kind of support as part of ‘normal lessons’!

Even more curiously, these figures aren’t closely- related to the proportion of free school meals pupils at the school. Teachers in more affluent schools reported using just as many readers and scribes as those in more disadvantaged schools, even though we know they will have far fewer non-native English speakers or children struggling with literacy.

So where are all these readers and scribes that are supposedly being used in schools under ‘normal practice’ coming from? They are being taken from other classrooms! Half of all teachers (except those in reception) report that their TAs were lent to the SATs effort during the exam week.

So, should we worry about this situation? Schools probably don’t feel they are ‘cheating’. Instead, what we have are 50 shades of playing the system. If teachers and schools must administer a system that will be used to judge them then ambiguous rules will get stretched to the extreme.

Legal Highs: Revision Classes for SATs

There are other things that schools can do to boost their results which are not within the maladministration category and more within the ‘booster’ label, on the basis that these interventions should also mean pupils improve their skills. One of these is revision classes.

11% of teachers said their school held booster classes over the East holidays with schools in poorer areas more likely to do so.

London and the East Midlands schools were particularly likely to get pupils in over the break. North West teachers, however, seemed to value their time off much more!

Conclusion

Given the evidence that teaching assistants are being used in dodgy ways to boost SATs results we cannot conclude that the current system is okay. Teachers are not necessarily up for massive change, however. A lot of year 6 teachers are not up for teacher-assessment of coursework. More people want to keep some kind of testing at 11 than want to get rid of it.

There are a few solutions on the table.

- Tests could be administered by secondary schools who have more experience of external exams. It is also easier to do spot checks in secondary schools as there are many fewer of them.

- The level of reader and scribe use needs to be analysed carefully by the Standards and Testing Agency, with the rules made much clearer.

- If teacher-assessment is the way forward then methods for making it less onerous and more reliable (potentially via something like No More Marking) need to be worked on with teachers.

What do you think?

Please do share your views with us on twitter @TeacherTapp or drop us a line hello@teachertapp.co.uk, or send us feedback via the app using the menu button in the top left-hand corner. What else should we be asking to find out more on this topic?

Finally, we know you love the tips, so here they are for last week…

- How KS2 value-added will be calculated from next year

- No written marking

- How much attention are you paying to attention in the classroom?

- A longer read on working memory

- Understand the power of feedback via Berger’s Butterfly

- Standardising marking is a loser’s game

- No staff meetings is the goal

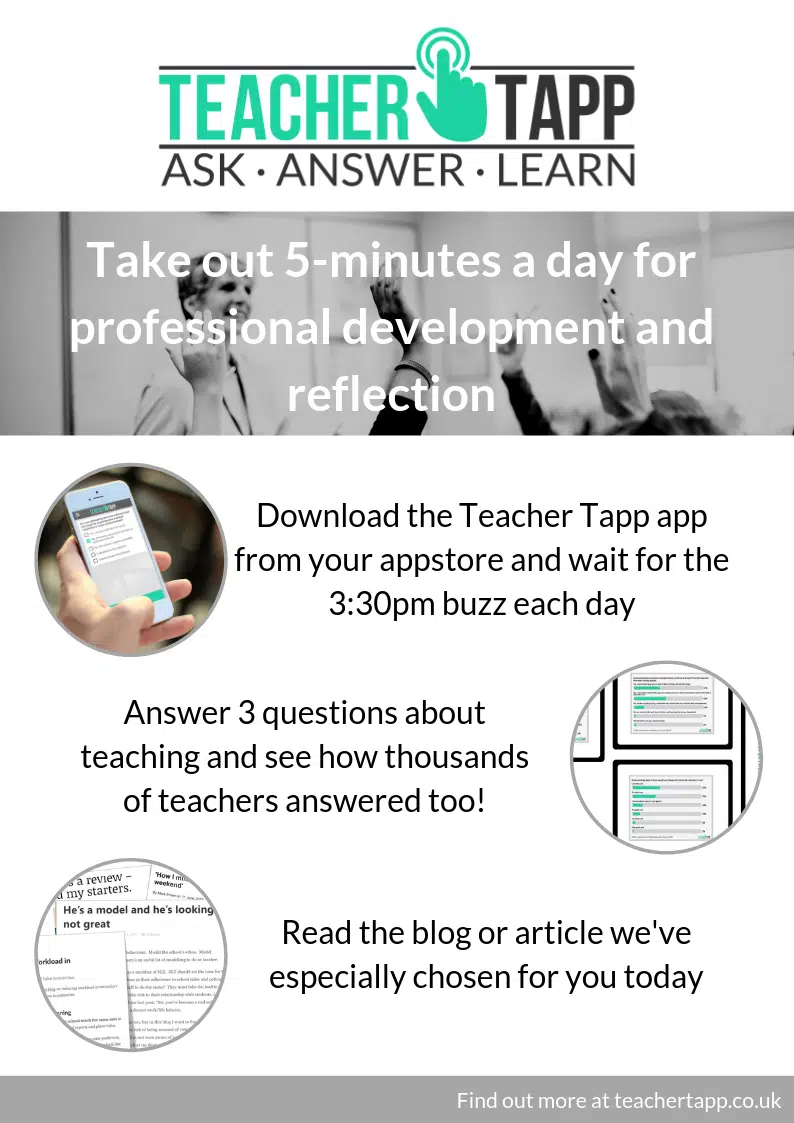

And don’t forget to tell your teaching colleagues all about Teacher Tapp!

We’ve even got a poster to put in your staffroom